Michael Barrett

Black Archives Sweden has spoken to the curator Michael Barrett about his work and relation to family archives.

How do you work with (relate to) your family archive: photographs, films, sound collections, memories, oral histories?

I have a bipartite family archive. My white mother’s family is kept alive through an oral archive that bubbles to the surface at family reunions as we browse through photo albums. My black father’s family archive consists of silences. It is only through hard work that I have been able to access it. My dad was a quiet person, and he came from a society of silence. When he left Jamaica, it was still a British colony, deemed as a place without a history of its own. He passed when I was nineteen years old and since then, I have single-handedly pieced words and relatives together in the hopes of keeping that part of me alive.

Two building blocks that have shaped my family archive are: Genealogy research through public archives around the world and the digitization of my dad’s photographs. My dad was an enthusiastic amateur photographer. He photographed constantly, especially when he came to Sweden in 1963. As children, my sisters and I were already tired of always acting as models for his photos. But he also photographed his friends in their homes and in public spaces in Gothenburg, Linköping, Malmö and Stockholm, preferably of other black people that he would encounter.

You have shared with us a visual material that is connected to your family. Why this particular material?

The photo showcases my father with his first wife in Kingston, Jamaica, during or right after the Second World War. They both worked at a camp for European prisoners of war. When the war ended, she travelled back to the Bahamas, pregnant with my half-brother Edward. The idea was that Dad would follow, but something happened, and he gradually began a journey that would eventually lead him to Sweden. Edward never got to meet his dad and had to grow up with that void. A couple of years ago, I was able to locate Edward in Florida and we’re now in touch. For me this is a typical story of the African diaspora. The Atlantic keeps us intertwined. We live in the here and now but simultaneously also within our histories and in the many cultures and contexts that bring us together.

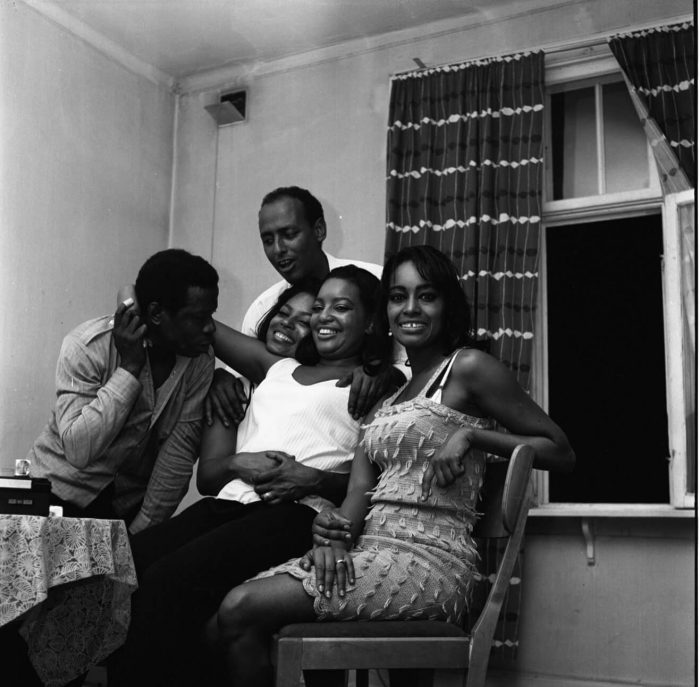

This photo (from the beginning of the 1970s?) really doesn’t have anything to do with my family, except for the fact that it was my dad who took the picture. For me it partially symbolizes something that I missed while growing up in a small Swedish town, namely a black community. Where I could exist in various ways without constantly being on guard. On the other hand, the image speaks to the imagined community of black people that remained strong within my dad and transcends places and continents through the diaspora. In contrast to the black community emerging in Sweden today, I think the 1960s were different, as there were very few black people here and many of them knew each other. Furthermore, the Black Power movement, Pan-Africanism and Négritude were very influential ideas at that time.

What does the (black) archive mean to you?

At first, I thought of my dad’s photo archive as silent as he was. Most of the people in the photos are completely unknown to me. But now I realize that even completely unknown people can speak through the images and tell me something that I did not know. Most of all, they exhibit something many in Sweden do not know about or want to know about, that black people have existed here for a long period of time. We have lived, worked, loved, felt despair, hoped and survived.

About Michael:

Michael Barrett is a researcher and curator at the Museums of World Culture, where he is responsible for the collections from the African continent. During his leisure time, he tries to understand his Afro-diasporic family history that extends from Sweden to the Atlantic world, Jamaica, England, United States and West Africa.